Source: Michael M. Santiago / Getty

Gibbs Knotts, Coastal Carolina University and Christopher A. Cooper, Western Carolina University

Holding hands with other prominent Black leaders, the Rev. Jesse Jackson crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, on March 9, 2025, to commemorate the 60th anniversary of “Bloody Sunday.” Like several survivors of that violent day in 1965, when police brutally attacked civil rights protesters, Jackson crossed the bridge in a wheelchair.

Jesse Louis Jackson was born Oct. 8, 1941, in Greenville, South Carolina, a town firmly entrenched in the racially segregated Deep South. This time and place aren’t footnotes to Jackson’s life, but rather key facts that shaped his civil rights activism and historic runs for the U.S. presidency.

Growing up in the segregated South shaped Jackson’s attitudes, opinions and outlook in ways that remain apparent today. While he lived in Chicago for most of his adult life, he remained a Southerner. And other Southerners viewed him as such.

Jackson’s biographer David Masciotra said the South gave Jackson “a sense of the oppression and the persecution that he wanted to fight.”

As scholars of Southern politics, we see Jackson’s Southern identity as essential to understanding his life. Southerners often identify with the region, even after leaving the geographic South. As sociologist John Shelton Reed once wrote, Southernness has more to do with attitude than latitude.

A segregated childhood

In the South Carolina of Jackson’s youth, water fountains, bathrooms, swimming pools and lunch counters were all segregated. While white people his age attended Greenville High School, Jackson attended the all-Black Sterling High School, where he was a star quarterback and class president.

His experience of segregation shaped how Jackson views his life.

“I keep thinking about the odds,” Jackson told his biographer and fellow South Carolinian Marshall Frady in 1988, marveling at the “responsibility I have now against what I was expected then to be doing at this stage of life.”

“Even mean ole segregation couldn’t break in on me and steal my soul,” he later told Frady.

If Jackson had been white, a star student like him might have enrolled at Clemson University or the University of South Carolina. Or he might have said yes when he was offered a contract to play professional baseball.

Instead, Jackson rejected the contract because the pay would be approximately six times less than a white player’s and went North, to the University of Illinois.

He did not find a more welcoming atmosphere in Champaign, Illinois. According to biographer Barbara Reynolds, the segregation that he thought he had left behind “cropped up in Illinois to convince him that was not the place to be.”

In the fall of 1960, Jackson transferred to North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, a historically Black college in Greensboro, North Carolina, to complete his sociology degree.

His return to the South marked Jackson’s emergence as a leader in the growing Civil Rights Movement.

Greensboro was a center of this struggle, with large, regular demonstrations, often led by local students of color. Six months prior to his arrival in Greensboro, four Black students from North Carolina A&T refused to leave the whites-only Woolworth lunch counter, launching a sit-in movement that soon drew national attention.

Jackson himself led protests to integrate Greensboro businesses. After one pivotal student march on City Hall, he was arrested and charged with inciting a riot. In jail, Jackson wrote a “Letter From a Greensboro Jail,” a rhetorical tip of the hat to Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.”

A move north

Jackson’s second move north, in 1964, stuck.

Like so many other Black Southerners who participated in what later became known as the “second great migration,” Jackson went to Chicago. He attended Chicago Theological Seminary, inspired not by a deep love of scripture but by what Jackson perceived as the church’s ability to do good on this earth.

As North Carolina A&T’s president, Dr. Sam Proctor, advised Jackson, “You don’t have to enter the ministry because you want to save people from a burning hell. It may be because you want to see his kingdom come on earth as it is in heaven.”

Jackson thought his time in Chicago “would be quiet and peaceful and I could reflect.”

It was anything but. Following the path of King and other religiously inspired civil rights activists, Jackson continued his civil rights organizing, leading Operation Breadbasket, an initiative of King’s to boycott businesses that did not employ Black workers.

Afro American Newspapers/Gado/Getty

Presidential aspirations

Over the next few years, Jackson took on ever more high-profile organizing, patterned after the life and work of King – another Southerner. As the former King aide Bernard Lafayette once said, “I mean, he cloned himself out of Martin Luther King.”

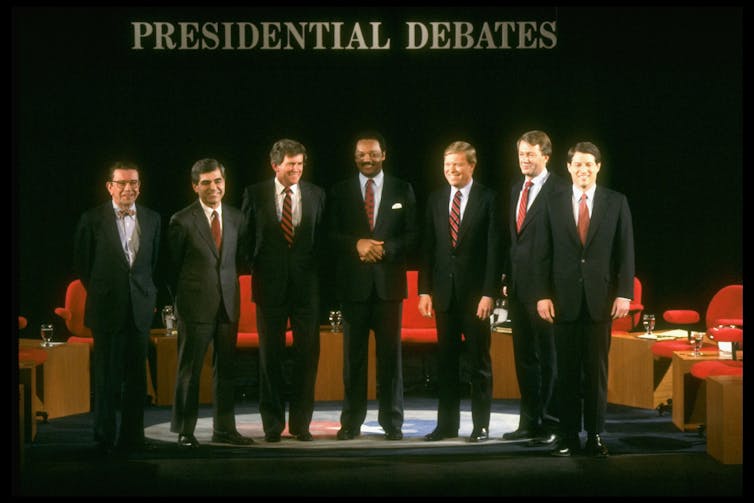

In 1984, Jackson turned to politics. He became the second African American to run for the nation’s highest office, following in the footsteps of Shirley Chisholm and her 1972 candidacy.

Announcing his bid, Jackson pledged to “help restore a moral tone, a redemptive spirit, and a sensitivity to the poor and dispossessed of this nation.”

But the campaign always represented more than a policy platform. Jackson wanted to mobilize more Americans to vote and to run for office, especially the “voiceless and the downtrodden.”

Jackson finished third in the 1984 Democratic primary but with a remarkably strong showing, taking 18% of all primary votes. He performed especially well south of the Mason-Dixon Line, winning both Louisiana and the District of Columbia. He also performed well in the Mississippi and South Carolina Democratic caucuses.

This surprising success inspired Jackson to run for president again. In 1988, he did even better, winning nearly 7 million votes and 11 contests, and sweeping the South during the primary season.

Diana Walker/Getty Images

He won the South Carolina caucuses and the Super Tuesday states of Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi and Virgina. In his second run, Jackson more than doubled his share of the white vote, from 5% in 1984 to 12% in 1988.

Jackson finished second in the Democratic primary to Massachusetts Gov. Michael Dukakis, who would go on to lose the 1988 presidential election to George H.W. Bush. But Jackson’s strong results solidified his position as a major figure in American politics and a power broker in the Democratic Party.

A towering figure in American politics

Jesse Jackson’s two presidential runs fundamentally altered the U.S. political landscape.

Beyond being the first Black candidate to win a state primary contest, Jackson also helped end the primary system by which the winner of a state would receive all the state’s delegates. Jackson claimed the system hurt Black and minority candidates and advocated to implement reforms that had been first recommended following the 1968 Democratic primary.

Back then, the party had pushed for a system in which delegates could be allocated based on the proportion of the vote won by each candidate, but it wasn’t adopted in every state.

Starting in 1992, following Jackson’s intervention, candidates receiving at least 15% of the vote officially received a proportion of the delegates. These reforms opened up the possibility that a minority candidate could secure the Democratic nomination through a more proportional allocation of delegates.

Jesse Jackson’s background also reinforced the importance of the Black church in Black political mobilization.

Perhaps most importantly, Jackson expanded the size and diversity of the electorate and inspired a generation of African Americans to seek office.

“It is because people like Jesse ran that I have this opportunity to run for president today,” said Barack Obama in 2007.

Buyenlarge/Getty Images

The long Southern strategy

Jackson’s political rise coincided with and likely encouraged the exodus of racially conservative white voters out of the Democratic Party.

The Republican Party’s Long Southern Strategy – an opportunistic plan to cultivate Southern white voters by capitalizing on “white racial angst” and conservative social values – had been underway before Jackson’s presidential bids. But his focus on social and economic justice undoubtedly helped drive conservative Southern whites to the GOP.

Today, some political thinkers question whether a distinct “Southern politics” continues to exist.

The life and career of Jesse Jackson reflect that place still matters – even for people who have left that region for colder pastures.![]()

Gibbs Knotts, Professor of Political Science, Coastal Carolina University and Christopher A. Cooper, Professor of Political Science & Public Affairs, Western Carolina University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()

SEE ALSO:

From Lunch Counters To Flash Mobs: Black Activists Birth A New Civil Rights Movement

Examining Nat King Cole’s Legacy Through The Lens Of Civil Rights